Why the current system does not respond to the crisis quickly and effectively:

Politicians still emphasize what has already been done for climate protection while science and environmental associations alarm that these measures are "too little and too late". We have taken a closer look at the phenomenon and compiled the structural facts for the insufficient action in the current system. When it becomes clear where the challenges and limits of the current system lie, such an analysis may open the view for alternative approaches, such as our model of personal tradable emissions budgets as an ecological basic income for all citizens. Because without a radical change of course in climate policy, we are likely to face major problems.

Climate protection caught in a vicious circle of diffusion of responsibility, national interests and global necessities

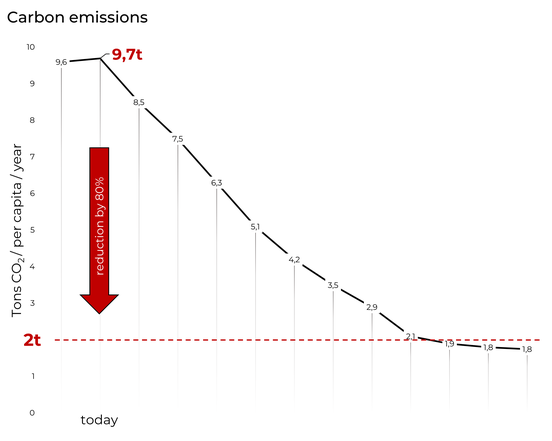

Many believe that climate protection is a matter for politicians, as they are responsible for legislation for the common good. Or it’s an industrial matter, since the emissions ultimately come from industry’s chimneys, Or it’s even the neighbor’s job to drive a smaller car and fly less on vacation. Most people are not even remotely aware of the effort it would take to even limit GHG to an acceptable level. For instance: In Germany, the average CO2 per capita consumption is about 10 tons per year. In order to limit global warming to approximately below 2 degrees, we would have to reduce this to less than 2 tons per person. This corresponds to a necessary reduction of about 80 percent – across the board!

Obviously, restrictions and renunciation are not going to make this happen. Our consumption can only be reduced in this way to a limited extent, a very limited extent. The current political tools, nonetheless, still focus on limiting our fossil consumption by making it more expensive. However, increasing prices does not simultaneously create sufficient, realistic and sustainable consumption or mobility alternatives. There are several systemic and personal reasons making it difficult to act effectively in the face of impending disaster.

Politics, industry, society - or the diffusion of responsibility

"Politicians can't fix it, industry doesn't want to fix it,

and we citizens face an insurmountable task because of the size of the problem.”

Why is this so?

The political view:

In addition to party tactical considerations, politicians are always interested in retaining power and being re-elected - they mainly think in terms of legislative periods. Particularly in our democratic system, a government is always dependent on mass approval. Regulatory bans and constraints are not popular. A government also massively relies on a well-functioning economy which does not budget additional expenditures for climate protection. Climate protection investments make domestic products initially more expensive, thus reducing competitiveness on the international market. Apparently, forward-looking global decisions are nearly impossible to implement in a timely manner. In short, politics is bound by constraints, primarily supporting its most powerful clientele. A government aiming to implement effective climate change measures automatically commits political suicide. Given the urgency of our crisis, this makes it particularly difficult to act quickly and effectively on climate policy. It is often not possible to achieve much more than a minimum compromise as shown, for example, by the bitter discussions surrounding Habeck's Building Energy Act (GEG), the escalating dispute over the reduction of subsidies in the agricultural sector and the latest debates surrounding the imminent reduction of CO2 fleet limits for the automotive industry.

The systemic intertwining of business and politics thwarts their actual mission - to act for the benefit of all people. This is a vicious circle, stymying forward looking action in the interest of future generations.

Viewed from the industry side:

The primary goal of industry is growth and profit, not climate protection. After all, the industry generally operates within the legal framework. Converting production to climate-friendly processes initially impacts competitiveness - also in an international context. Although there is an interest in an environmentally friendly image, it remains to be seen to what extent consumers are willing to pay more for it. Manufacturers fear that their customers are hardly willing to accept a higher price for genuine CO2-free products and a clear conscience.

Since the costs of fossil fuel damages have still not been priced in, and billions in subsidies continue to be injected into their use, they are supposedly more favorable from an economic point of view. No company can be expected to make uneconomic decisions voluntarily and risk a competitive disadvantage. In addition, Europe's industry worries it will not be able to compete with Chinese and U.S. American prices, for example, who have far less stringent requirements. As a result, industry sees little reason to transform on its own initiative. And the truth is that no industry produces for its own sake, but ultimately according to the demand of all of us – including goods produced abroad (e.g. China, ...). All too often, chasing short-sighted economic efficiency takes precedence over environmental protection. These are simply the rules in the game of capitalism in an increasingly deregulated market economy.

What role do we consumers play?

None of us wants rampant climate change. But the moment protective measures affect our personal comfort zone or own wallet, willingness and acceptance drop significantly. Isolated, individual efforts have very little influence and resignation is often the result. Because personal action or omission has virtually no effect on the big picture. A lack of climate-friendly consumption alternatives on a sufficient scale, which can also be implemented in a low-threshold manner, does the rest.

"Yes, sure, climate protection is important,

but surely we have more pressing problems right now!"

Besides, we are just weary of the endless array of disasters. Adaptable as we are, we become habituated to even the greatest evils of our time. Superlatives get old. Constantly bombarded with terms like "catastrophe," "flood of the century" or "hottest summer on record," we eventually stop listening. We are saturated - understandably so. The climate crisis is often the elephant in the room. No one sees what’s not happening in their front yard. Melting glaciers are far, far away. But ignored problems do not simply go away. The climate crisis is the central threat to our future existence. Yet it still does not receive the attention it deserves. Of course, the climate crisis is not the only hot topic, but it is intricately entwined with all others. Waiting for the market to develop the right technologies to save us from global warming in the nick of time is dangerous wishful thinking. New technologies do not appear out of nowhere and immediately solve our problems. Nothing in human history supports the idea. Relying solely on innovations to save the planet is a form of denial.

The vicious circle of inaction is a result of conflicting goals between ecological awareness and economic constraints, of the diffusion of responsibility and of the dichotomy between self-interest and morality. Climate protection simply cannot be left to voluntary individual, industrial or governmental action.

We must decouple the solution from all these different, predominantly short-term special interests and establish a new, effective system. A system that works according to the polluter pays principle. A system that takes into account the smallest unit on the market – the consumer and their enormous influence on industrial production processes. A system that implements an ecological basic income, placing the power and control of climate protection completely in the hands of all people. A system in which market economy laws function in harmony with ecological sustainability.

The perfidious blame game or the limits of restriction and renunciation

Whatever motivates our lack of climate crisis action, it should never be about guilt or ugly comparisons, i.e. "your consumption is worse than my consumption." No one should feel attacked. Finger-pointing leads only to an inevitable division of our society. We all participate in this system that created the current state of our environment. We are all obligated to find our way out together, without leaving anyone behind. In this game, all participants are equally responsible, and yet no one is really to blame. That's why we need to change the rules of the game. We need a paradigm shift - a systemic approach that accommodates the hugely diverse personal realities, individual consumer preferences and conflicts of interest with an absolute minimum of intervention.

We direly need a model that erects ecological guard rails and decouples climate protection from blame game. A model that allows every citizen to decide for themselves – by means of personal emissions budgets – how they integrate climate protection into their lives - not whether they do. A model that allows consumers maximum freedom within very clearly defined ecological limits for everyone. Such a concept relieves policymakers of the need to enact, implement, and monitor small-scale and often unpopular regulatory measures.

Trusting to voluntary individual savings is a climate policy pipedream.

"Too little and too late"

or why a CO2 tax and EU emissions allowance trading (EU-ETS) are not enough

With the current EU-ETS and CO2 tax we will probably miss the climate target. Neither an increase in price nor a waiver will result in a sufficient production of climate-friendly goods. In addition, the surcharges are anti-social, disproportionately burdening lower-income households.

Politics is always confronted with the challenge of upholding national economic interests while complying with agreed emission reduction quotas. If industrial emissions certificates become too scarce or their prices rise too high, international competitiveness is jeopardized. As a result, energy-intensive companies outsource their production to countries with less stringent regulations (carbon leakage). In order to prevent this, certificates are still being issued to some companies free of charge. All the same, fossil fuel produced goods are still imported, counteracting our efforts to protect the climate.

Price hikes do not create much needed consumer options

Attempts to reduce fossil fuel consumption by making it more expensive is also regularly undermined. Public, economic and oppositional outcry waters down these efforts until they are nothing but a placebo. Case(s) in point: The current push to suspend the CO2 tax increase to 40€/ton; the moratorium on tightening building energy efficiency standards (EF55), or the sleight of hand: "merging of sector targets" to make up for the insufficient emission reduction in some areas. The German government installed a fossil fuel carbon tax in the heating and transport sectors in January 2021. The fossil fuel price increase was intended as an incentive to reduce heating energy and gasoline consumption. But only a few people are leaving their cars at home. How else are people supposed to get from A to B? Not everyone has access to buses and trains. Various measures were considered to relieve the financial burden on citizens: Lowering the value-added tax for energy and fuel, abolishing the EEG levy, increasing the commuter allowance, paying energy subsidies for those entitled to housing subsidies, etc. And, obviously, all these understandable compensatory measures counteract the actual purpose of the carbon tax. And with an emissions ceiling (cap) still missing, the carbon tax is not going to sufficiently reduce fossil fuel consumption.

Obviously, the idea that raising prices would inspire consumers to change their habits has failed miserably. How could it be otherwise? We consumers do not have nearly enough climate-neutral alternatives. The enormous gasoline and heating price increases have reduced CO2 in the single-digit percentage range. A faint whisper in the roar to reduce per capita consumption to below 2 tons of CO2 / year.

In addition, a climate policy based on higher prices is not expedient for various other reasons. First, there is the erroneous assumption that the higher price, the lower the demand. Not so. There is always price elasticity. It is true that an increase in price normally triggers reduced demand, but not proportionately. Not by a long shot. People may resent paying the added taxes but pay them they will. Therefore, the (over)use of the atmosphere with climate-damaging gases will not be reduced to a sufficient extent by increasing the price, let alone limiting it. In principle, everyone can continue to emit unlimited amounts, only the costs increase. A concrete limitation of emissions by budgeting is missing!

Why our monetary system can’t solve the climate crisis

The simplified equation "money = consumption = emissions" not only brings to light the ubiquitous climate and emissions inequity between rich and poor, it also describes the inseparable causality between wealth and climate-damaging emissions. This will continue as long as our consumer goods are not generally produced in a climate-neutral manner. Increasing the price of goods and services in the fight against climate change is of little use. Money saved by cutting back, doing without or using more efficient technologies in one place is usually spent again elsewhere - e.g. on an additional vacation (rebound effect). This is just one more reason why it is essential to separate effective climate protection and our consumer-related emissions from the monetary system - through a complementary climate currency!

Lack of ecological cost transparency

Money alone can never truly reflect our consumption’s burden on ecosystems. There are so many cheaply produced products in our consumer society and are consequently sold at a very low price. Their production or operation, however, entails extremely high ecological costs. The carbon tax in the product price is nearly impossible to trace and is lost among other cost factors. So how are consumers supposed to choose a more climate-friendly product?

All this shows that certificate trading and price hikes will never reduce emission enough to reach the climate target. We need a model that is able to reconcile national interests with global necessities. Drastically reducing emissions to meet planetary boundaries is not an option, it’s an obligation!

The NGO SaveClimate.Earth proposes an effective, socially just alternative. Their proposed solution establishes a consistent polluter-based system at the consumer level. Personal, tradable, emissions budgets trigger a change in consumer habits that generates enormous pressure, motivating industries to defossilize production processes - significantly increasing green consumer alternatives. Industry will produce what we can afford within our limited budgets.

The climate crisis is a global, multi-causal and multi-layered problem. We cannot combat it with singular regulations. We need a scalable framework for action that allows us to respond to ecological challenges swiftly and appropriately. Only by sustainably shaping our economic, consumer and lifestyle patterns, by giving ecological and social aspects the same importance as economic ones, will we be able to fulfill our responsibility for future generations.

To achieve this, we need a paradigm shift

- that will ensure that greenhouse gases produced by our consumption are fully recorded, transparently mapped, and fairly accounted for.

- to a system which allows consumers complete freedom within clearly defined limits for everyone, without exception.

- which guarantees we meet our climate target precisely and flexibly.

- towards a model which is relatively simple to administer and contributes to reducing social inequality.

- away from measures that rely on price increases, restrictions and waivers, that disproportionately affect lower-income households, and that drive domestic emissions-intensive industries abroad, where less stringent environmental regulations apply.

- away from small-scale, often unpopular measures, toward personal, tradable emissions budgets.

There would be no more long and weary political debates about regulations. Consumers trigger and support the necessary transformation processes in the economy through their purchasing decisions, demanding more favorable ecological prices. A climate currency that is decoupled from the monetary system automatically applies the most suitable methods or techniques that will achieve the best emissions reduction with the least effort. Without additional price increases or governmental or regulatory interventions.

"The NGO SaveClimate.Earth,

an organization for sustainable economy,

has developed a concept for tradable, personal, emission budgets,

which could be immediately introduced at EU level and gradually expanded worldwide."

There are answers to

- why emissions trading at the individual level is superior to industrial certificate trading and the carbon tax.

- how personal, tradable, emission budgets is an effective and socially-just counter-design to all current measures, and how this can guarantee we meet our emission target.

- what the complementary resource currency ECO (Earth Carbon Obligation) as a global CO2 equivalent could look like.

- how the monthly payment of the ECO works as an ecological basic income in the form of a personal, tradable, emissions budget.

- how a separate emissions price tag in the climate currency ECO ensures the true climate impact of products can be compared with each other.

- how we pay for our individual CO2 consumption with our personal climate account.

This page was translated with the help of DeepL